Archaeological Discoveries: Magna Carta and Ancient Tombs

- Martin Low

- May 30, 2025

- 18 min read

Archaeology often conjures images of ancient ruins and buried artifacts, yet it also encompasses the study of historical documents and cultural heritage. Recent findings — from a medieval charter in a university archive to newly unearthed royal tombs in Egypt and hidden cities in South America — have enriched our understanding of the past. This article examines how archaeological discoveries in diverse contexts challenge and deepen historical narratives. We will explore a recently rediscovered copy of the Magna Carta, major tomb discoveries in Luxor’s Dra’ Abu el-Naga necropolis, and significant archaeological finds at key South American sites. Throughout, the focus is on the historical context and implications of these finds, rather than on excavation techniques, showing how each discovery sheds new light on human history.

Archaeology of Medieval Manuscripts: The Magna Carta

One might not immediately think of archaeology when considering medieval manuscripts, but historical documents can be seen as artifacts whose discovery or rediscovery has profound historical impact. The Magna Carta, a 13th-century English charter, is one such document. It was originally issued in 1215 by King John to guarantee certain rights and limit royal power. Over the centuries it was reissued by later kings, and some 200 original charters were produced by 1300. Only 24 medieval originals survive today, many of them in British archives. One recent startling discovery concerns a copy long thought to be a mere reproduction of the Magna Carta: in May 2025 British scholars announced that Harvard Law School’s copy is in fact an authentic 1300 issue from King Edward I.

Archaeology of Harvard’s Rediscovered Magna Carta

In the 1940s Harvard Law School acquired an old manuscript labeled as a “copy” of the Magna Carta, reportedly made in 1327. For decades it was a forgotten library item of little value. In 2024–2025, medieval historians David Carpenter (King’s College London) and Nicholas Vincent (University of East Anglia) studied digitized images of the manuscript and concluded it is actually an original Magna Carta from 1300. This reclassification makes it “just one of seven” known surviving copies from Edward I’s 1300 issue, transforming its significance entirely. The discovery was announced in May 2025, and scholars praised it as a “cornerstone of freedoms” and “one of the world’s most valuable documents”.

This revelation has concrete implications for the history of Magna Carta. For example, Harvard’s copy increases by one the already small number of surviving originals from that period, shedding light on how widely the charter was distributed. It also shows that valuable artifacts can lie hidden in plain sight in archives. As Professor Carpenter observed, the manuscript “deserves celebration… as an original of one of the most significant documents in world constitutional history”. In practical terms, historians can now examine this 1300 original to compare its wording and seals with other copies, clarifying how Magna Carta was understood in different regions of England.

The Harvard find reminds us that archaeology of documents – carefully analyzing old manuscripts – can be as enlightening as unearthing tombs. It forces a reassessment of the Magna Carta’s material legacy. For example, before this discovery most knowledge of surviving charters was based on the 24 known originals (including two in the U.S. National Archives and one in Australia). With Harvard’s newly authenticated charter, scholars must update catalogues of Magna Carta originals and consider why this piece was misidentified for so long. It suggests we may need to reexamine other “copies” in libraries worldwide for overlooked originals.

Overall, the archaeology of Harvard’s Magna Carta underscores how historical understanding evolves. The charter itself was a steppingstone toward the rule of law, influencing constitutions globally. In finding another original copy, historians gain fresh material for studying its wording and distribution. As Nicholas Vincent remarked, Magna Carta is “an icon of the Western political tradition”. This rediscovery not only celebrates an item once paid for as a “curiosity”, but it also serves as a reminder that even medieval documents can yield new surprises when reexamined.

Archaeology of Ancient Egyptian Tombs: Luxor Discoveries

In contrast to medieval documents, archaeology in its traditional sense often involves excavating sites and tombs. Egypt’s Nile Valley, especially around Luxor (ancient Thebes), is one of the world’s richest archaeological regions. Luxor’s necropolis contains royal tombs like those in the Valley of the Kings and numerous tombs of nobles and priests. In 2025, Egyptian archaeologists reported several significant tomb discoveries in the Luxor area, particularly in the Dra’ Abu el-Naga sector. These finds provide a window into the lives of non-royal officials during the New Kingdom era (circa 1550–1070 BCE) and refine our picture of Thebes as a major administrative center.

Archaeology of Luxor’s Dra’ Abu el-Naga Necropolis

Dra’ Abu el-Naga is part of the western Theban necropolis, north of the Valley of the Kings. It was historically a burial ground for nobles and high-ranking officials, especially in the 18th and 19th Dynasties. In late May 2025, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced the discovery of three New Kingdom tombs at Dra’ Abu el-Naga. These tombs date from roughly 3,200 years ago and belonged to notable officials. According to the reports, the tombs were found by an Egyptian archaeological team during the current excavation season.

Photographs released by officials show courtyards and burial shafts. Inscriptions inside the tombs identified the occupants and their titles. The tomb of Amun-em-Ipet (also spelled Amum-em-Ipet) belongs to a man of the Ramesside period who served in the great Temple of Amun in Thebes. Although much of this tomb’s decoration was damaged or incomplete, surviving scenes depict funerary offerings and a banquet – typical New Kingdom tomb art – and a depiction of the deceased’s servants carrying a funerary bed and chest. The walls are painted with figures of seated individuals and religious symbols, although parts of the tomb were later reused (a breach in one wall created an additional chamber).

Two other tombs date to the 18th Dynasty (circa 1550–1295 BCE). One belonged to Baki, who was identified by an inscription as “supervisor of the grain silo” – a high administrative post managing grain storage. His tomb features an elongated courtyard and multiple halls, with a long corridor-like courtyard and an unfinished inner shrine. The third tomb is identified only by the initial “S” and belonged to a man who held several titles: supervisor of the temple of Amun in the northern oases, mayor of the northern oases, and scribe. His tomb design is simpler: a small courtyard leading to a shaft, then a transverse hall and an unfinished longitudinal hall. Inscriptions in this tomb highlight his broad administrative authority over temple affairs and regional governance.

These finds are remarkable because they give precise names and roles for the tomb owners, which is relatively rare for non-royal burials. For example, we now know that Amun-em-Ipet was connected to the great Amun temple, that Baki managed grain storage (a vital resource in ancient Egypt), and that “S” combined religious, administrative, and writing duties. This adds insight into the bureaucracy of New Kingdom Egypt: it confirms that the state had specialized officials overseeing temples, agriculture, and regional administration. Daily News Egypt explicitly noted that “this discovery adds valuable insight into the roles and lives of officials during the New Kingdom”.

Archaeologically, the discovery of these tombs in Dra’ Abu el-Naga reinforces how much remains to be uncovered even in well-studied areas. Luxor has been excavated for centuries, yet new tombs continue to emerge during ongoing work. These tombs also illustrate Egyptian burial customs for elites: each tomb has a courtyard, halls decorated with scenes, and burial shafts. They show that even officials whose names we now recover were buried with care, though on a smaller scale than royal tombs. Notably, Minister Sherif Fathi called the find a “major scientific and archaeological milestone,” emphasizing that it will attract more interest in Egypt’s cultural heritage.

As archaeological evidence, these tombs enhance our understanding of New Kingdom Thebes in two ways. First, they confirm that Dra’ Abu el-Naga continued to be used for high-status burials across dynasties, not just for one reign or family. Second, by identifying the tomb owners and their official titles, they allow historians to connect names in the archaeological record with historical events or administrative structures. In other words, archaeology here complements written history: where textual records might mention a “supervisor of grain,” the tomb provides a name and a face (through a depiction).

Archaeological Insights from New Kingdom Tombs

Beyond the Dra’ Abu el-Naga finds, 2024–2025 saw several related discoveries in Luxor, reinforcing the picture of the area’s wealth of archaeology. In January 2025, Egyptian archaeologists announced ancient rock-cut tombs and burial shafts at Deir al-Bahri, the site of Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. In late 2024, a tomb with 11 sealed burials from the Middle Kingdom was excavated near the Temple of Hatshepsut. These show that both the 18th and Middle Kingdoms left behind significant tombs in the Theban area. Each discovery helps fill gaps about periods of Egyptian history. For instance, the Middle Kingdom tomb (around 1800 BCE) in South Asasif suggests continued use of royal temples for burial even outside their most famous golden ages.

Taken together, these discoveries challenge the notion that all major finds in Luxor have been made. Instead, they underscore Luxor as an ongoing source of archaeological revelations. They also highlight a trend: many recent finds were made entirely by Egyptian teams (sometimes with minimal foreign oversight), reflecting the growth of local expertise in archaeology. As Daily News Egypt noted, they “highlight the growing success of Egyptian-led missions” in uncovering heritage.

For students of history, these finds refine our understanding of the New Kingdom. While pharaohs and kings dominate textbooks, these tombs show the society around them. For example, identifying the tomb of Baki (grain supervisor) suggests how grain supply was managed by a specialized official. It hints at the complexity of the Egyptian economy and administration. Similarly, the multipurpose roles of the man “S” suggest that individuals could hold both religious and civic offices, blending temple work with civil governance. Archaeology thus illuminates the often-overlooked links between religion, economy, and governance in ancient Egypt.

Archaeology in South America: Recent Discoveries

South America’s archaeological record spans ancient Andean empires, Amazonian societies, and other cultures that predate European contact. Recent findings in this region have been striking for their novelty and scale. We will discuss discoveries at four major South American contexts: the Nazca Desert of Peru (famous for the Nazca Lines), the cloud-forests of the Chachapoya civilization (Gran Pajatén in Peru), the Amazon basin, and coastal Peru’s ancient temples. Each has reshaped historical perspectives.

Archaeology of the Nazca Desert Geoglyphs

The Nazca Desert of southern Peru is world-famous for the Nazca Lines – gigantic ground drawings of animals and shapes created by the Nazca culture around 500 BCE to 500 CE. In September 2024, researchers announced the discovery of 303 previously unknown geoglyphs in the Nazca region using artificial intelligence and drones. This find nearly doubles the number of known figurative geoglyphs at the site (from about 800 to over 1100), and it dates these figures to around 200 BCE, earlier than the large geometric designs.

The images include parrots, cats, monkeys, birds, and human forms, all smaller than the famous giant hummingbird or monkey patterns. They fill in the picture of how Nazca art developed over time. According to The Guardian, these new figures “provide a new understanding of the transition from the Paracas culture to the Nazcas”. The Paracas preceded Nazca and are known for intricate textiles and art. Finding 200 BCE geoglyphs suggests that drawing on the desert floor was a cultural practice well before the later Nazca workshops, and it sheds light on how one culture’s artistic traditions evolved into another’s.

The method of discovery itself is notable: researchers from Japan’s Yamagata University used AI pattern-recognition algorithms on thousands of hours of aerial video footage. This confirms that modern technology can accelerate traditional archaeology by finding sites that the human eye could easily overlook. As archaeologist Masato Sakai noted, “The use of AI in research has allowed us to map the distribution of geoglyphs more quickly and accurately”. In plain terms, computers helped find lines in the desert that drones recorded, making the previously isolated scratches visible on a large scale.

Historically, the Nazca geoglyphs have puzzled archaeologists: their function and meaning remain debated. By expanding the catalog of images, researchers can compare motifs and techniques across a broader sample. For instance, the discovery of early geoglyphs depicting similar animals might suggest ritual continuity or regional trade between Paracas and Nazca people. It could also mean the Nazca culture had cultural roots deeper in time than realized. As a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper explains, the AI-assisted survey “nearly doubles the number of known figures” and has major implications for Nazca archaeology.

In summary, the Nazca geoglyph discoveries have enriched our archaeological understanding by confirming that pre-500 BCE peoples in coastal Peru were making monumental ground drawings. This pushes back the timeline for geoglyph creation and emphasizes that Nazca was not an artistic anomaly but the outcome of a longer tradition. It also demonstrates how combining archaeology with technology can quickly change historical narratives.

Archaeology of the Chachapoya Ruins at Gran Pajatén

In the Peruvian Andes, recent archaeological work has also transformed views of the Chachapoya culture, often called the “Warriors of the Clouds.” The site of Gran Pajatén in northern Peru (Amazonas Region) was partly excavated in the 1960s, revealing stone-built temples with carved friezes and mosaics. However, much of this cloud-forest site remained hidden under dense vegetation. In May 2025, the Archaeological Institute of America reported that a new conservation project led by the World Monuments Fund has revealed over 100 additional structures at Gran Pajatén, far more than the 26 previously known.

These newly exposed buildings include residences, plazas, and ceremonial spaces. The scale is astonishing: what was once thought to be a single isolated ceremonial complex is now seen as part of a network of interconnected settlements. Archaeology Magazine quotes WMF Peru director Juan Pablo de la Puente Brunke: “This discovery radically expands our understanding of Gran Pajatén and raises new questions about the site’s role in the Chachapoya world”. In other words, Gran Pajatén was not a lonely mountaintop temple but a center of a more extensive society.

This changes historical interpretation of the Chachapoya civilization. Previously, Gran Pajatén’s remote location (perched about 2,700 meters altitude) had suggested it was a unique ritual site. Now, with hundreds of structures, archaeologists see it as a large city or capital of a wider territory, connected by paths through the jungle. The finds include dwellings arranged on terraces, water channels, and cemeteries. Even decorative stone mosaics and human-shaped friezes have been found on some buildings.

To see the impact on historical understanding, consider that Gran Pajatén is dated to roughly 800–1400 CE, a period that overlaps with late pre-Inca cultures. Earlier, Chachapoya societies were considered peripheral and mysterious. Now we know they built elaborate urban centers. This supports the idea (already suggested by other finds like Kuelap fortress) that the Andes had multiple advanced societies before the Incas, each with its own architecture and culture. The archaeology at Gran Pajatén shows that Chachapoya social organization was more complex than previously thought, involving large communal projects to build stone cities in difficult terrain.

In sum, the Gran Pajatén discoveries demonstrate how uncovering even a single site can reframe an entire civilization. Archaeologists have long known about Nazca and Inca, but Chachapoya remained understudied. With new structures revealed, scholars will reassess trade, warfare, and cultural exchange in northern Peru. It also underscores the value of international cooperation: satellites, ground crews, and funding have allowed archaeologists to clear thick jungle that hindered past research.

Archaeology of the Amazon Basin Cities

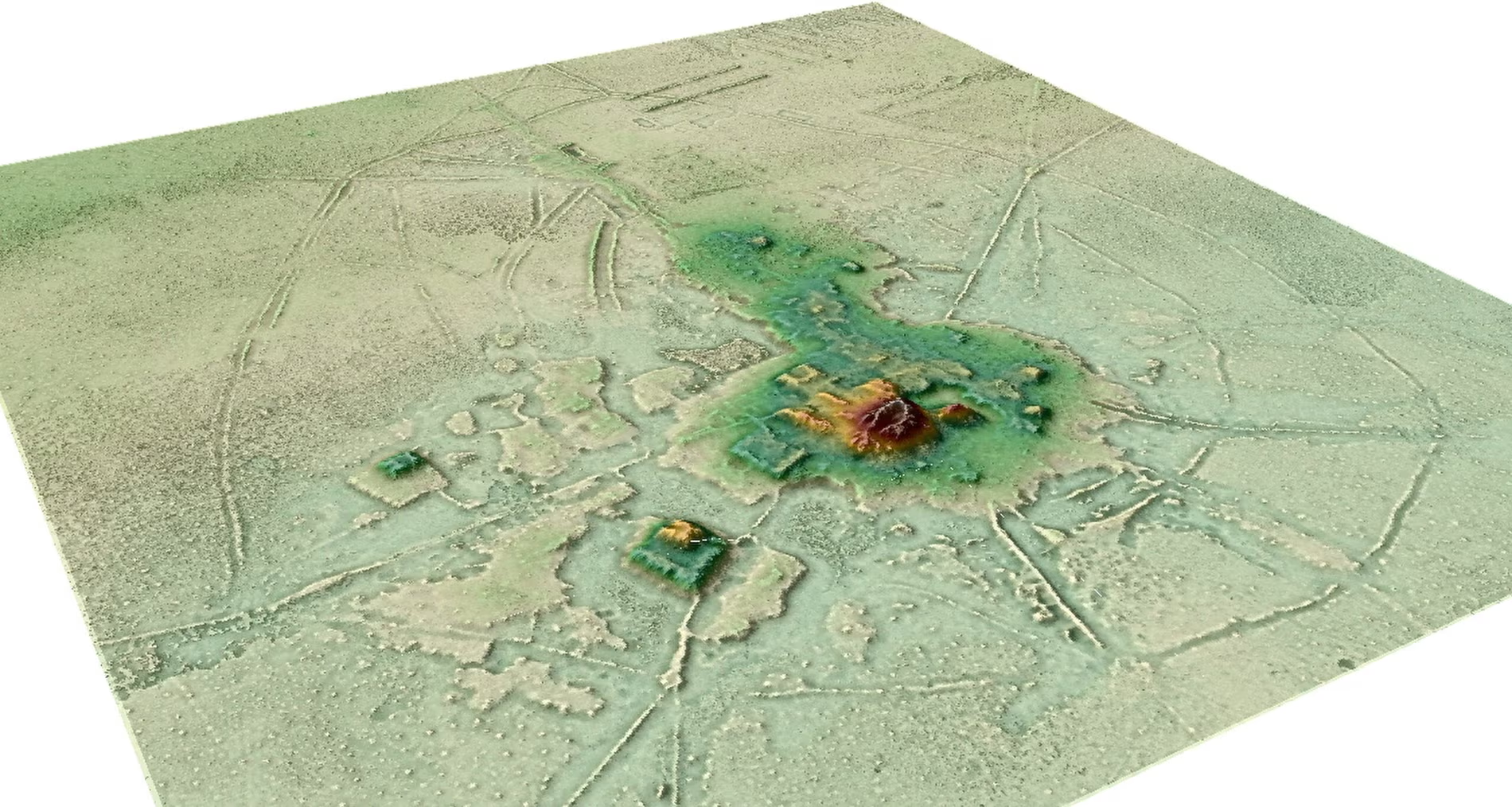

Archaeology of South America has most often focused on the Andes, but 2024 saw dramatic evidence that the Amazon Basin – long thought inhospitable for large societies – was home to large, complex settlements. In January 2024, the BBC reported on the discovery of a massive ancient city in the Amazon, in the Upano region of eastern Ecuador. Using LiDAR (airborne laser scanning) along with ground surveys, researchers identified about 6,000 earthen mounds and platforms arranged as houses and plazas, covering some 300 square kilometers. These features were connected by a system of roads and canals, indicating sophisticated urban planning.

This site dates to roughly 500 BCE – 100 CE, making it around 2,500 years old. It was inhabited for about a millennium, potentially by tens of thousands of people at its peak. Importantly, it predates by centuries any known highland South American city like Machu Picchu (built ~1450 CE) or Caral (earlier, ~2600 BCE, but in a different part of Peru). The Amazon discovery “changes what we know about the history of people living in the Amazon”. Prior to this, the prevailing view was that Amazonian groups were small, nomadic, or semi-nomadic forest dwellers. This site shatters that stereotype. As archaeologist Stephen Rostain, who led the research, explained: “This is older than any other site we know in the Amazon… it shows we have to change our idea about what is culture and civilization”.

The findings fundamentally challenge the “Eurocentric view” that the Amazon was empty of cities. Instead, they indicate that Amazonian peoples built cities with farms, fish ponds, and urban amenities, similar to contemporary civilizations elsewhere in the world. The use of LiDAR was crucial: by mapping ground contours under forest canopy, archaeologists could see the remnants of these platforms and roads. The BBC article emphasizes that people lived in “complicated urban societies” hidden under the jungle canopy.

This discovery joins other Amazonian finds (particularly in Brazil and Bolivia) that together suggest many “garden cities” were spread across the basin. For example, another Guardian report (Feb 2025) describes thousands of geometric earthworks and settlements found in Brazil’s Acre state using aerial scans. Together, these reveal that by the time of European contact, the Amazon was not an untouched wilderness but contained numerous populous landscapes managed by indigenous civilizations. The concept of terra preta (rich black earth) in Amazonian soil, long known by archaeologists, supports this: it shows that ancient people planted and enriched the soil.

In historical terms, the Amazon discoveries force us to reconsider pre-Columbian South America. We can no longer ignore the possibility that complex societies existed outside the Andes. These finds open questions about culture, language, and organization in the Amazon: did the Amazonian city have written records or a known name? What language did they speak? How did they interact with mountain cultures? As Antoine Dorison, co-author of the study, noted: “Ancient people lived in complicated urban societies,” overturning old images of the Amazon. We now see the Amazon was a cradle of civilization in its own right.

Archaeology of Ancient Peruvian Temple Sites

Coastal Peru has long been recognized for early monumental architecture, from the Caral-Supe civilization (around 3000 BCE) to later Inca sites. In July 2024, researchers announced a discovery at Zaña, Peru, of a 4,000-year-old temple and theater complex. These ruins are dated to roughly 2000 BCE, making them about 3,500 years older than Machu Picchu. Although smaller than a pyramid, this site is archaeologically significant as one of the earliest known ceremonial structures in the Andean world.

Archaeologist Luis Muro Ynoñán, who led the excavation, explained that the temple provides evidence about “the earliest religious spaces” in the region. Before this, archaeologists had limited knowledge of what Andean religious practice looked like more than 3000 years ago. The site includes a section of temple walls and an amphitheater-like space (possible performance area). Intricately carved stone depicting a bird-like creature (resembling art from Peru’s later Initial Period) suggests continuity of iconography.

By predating the Inca and even the Moche and Nazca cultures, this temple pushes back the timeline of organized religion and public ritual in the Andes. It implies that by 2000 BCE, people in coastal Peru were building communal sacred structures. This overturns any idea that religion in Peru only became organized later. As the Smithsonian article notes, “We still know very little about how and under which circumstances complex belief systems emerged in the Andes,” but now “we have evidence” of those early religious spaces.

Furthermore, archaeologists found human remains inside the temple, including individuals buried with offerings. This indicates the temple may have served both living rituals and funerary purposes, suggesting a complex set of beliefs. Large wall murals have also been uncovered, and paint pigment analysis (ongoing) could reveal trading networks. While detailed results await publication, it is clear that this site transforms our view of pre-Inca Peru: instead of a gap between Caral (earliest city) and the Moche, we now have a piece of 2000 BCE high-culture to fit in between.

In sum, the Zaña temple discovery is a prime example of how a single archaeological site can enrich historical understanding. It reveals that coastal Peru had architectural and religious complexity thousands of years ago, bridging the gap between early farming villages and later complex states. This may lead historians to rethink the development of Andean civilizations, recognizing a longer continuity of ceremonial architecture.

Archaeology of the Ancient Inca Capital (Cusco)

Finally, a 2025 discovery in the heart of the former Inca Empire underscores that even well-known sites hold surprises. Archaeologists have long speculated that underground tunnels ran beneath the Inca capital Cusco, connecting its temples and plazas. In January 2025, a team led by Jorge Calero Flores reported confirmation of a subterranean tunnel system under Cusco. Using ground-penetrating radar guided by clues from Spanish colonial texts, researchers identified passages following the city’s old road network.

Notably, they found a tunnel connecting the Inca Temple of the Sun (Qorikancha) with the fortress of Sacsayhuamán, over a kilometer apart. This passage runs below the colonial streets of Cusco. The Smithsonian article on this find highlights that Spanish chroniclers had written about such tunnels, but now archaeology has validated their accounts. In effect, the archaeologists have uncovered an “underground Cusco,” confirming that Inca builders dug passages mirroring their famous surface architecture.

Why does this matter? Sacsayhuamán is a monumental ceremonial complex north of Cusco, and Qorikancha was the religious center. A tunnel between them suggests ritual or administrative use, perhaps for priests or emergency movements. It also reveals the Inca concern for aligning sacred geography vertically as well as horizontally. Confirming the tunnel changes how historians see Cusco’s layout: it was not just a city of grand stone walls, but also an engineered underground space.

This discovery exemplifies how archaeology can intersect with history and legend. The Inca left no written language, so much of what is “known” comes from archaeology and Spanish chronicles. By matching modern technology to an old story, researchers have expanded our vision of Inca urban planning. It reminds us that even famous sites like Cusco have layers – literally – that can be peeled back by archaeologists.

In broader terms, the Cusco tunnel shows that South American archaeology is not confined to open digs; it can include geophysics. But the key point is that it enriches the narrative of the Inca Empire. It suggests that the Incas invested significant effort in underground construction, an element rarely visible in their ruins. This may prompt new questions about other Inca cities: might there be hidden passages yet to be found at places like Ollantaytambo or Machu Picchu?

Conclusion

From medieval Europe to ancient America, recent archaeological discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of the past. The chance identification of a 1300 Magna Carta in Harvard’s archives adds to the documented history of constitutional development and reminds scholars that written artifacts can be “rediscovered” much like buried relics. In Egypt, the unearthing of officials’ tombs in Luxor highlights the social structure and daily life of the New Kingdom that complement what royal tombs and papyri have already taught us. Across the Atlantic, the mapping of geoglyphs, temples, and even entire cities in South America reveals that complex societies thrived long before or outside of well-known cultures; each new site forces historians to adjust timelines and cultural models.

These findings share a common lesson: archaeology is a dynamic dialogue between past and present. New evidence can affirm, elaborate, or overturn long-held beliefs. The role of archaeologists is both as explorers uncovering artifacts and as interpreters crafting the story of humanity. Importantly, the discoveries discussed here were made possible not just by traditional digging, but by interdisciplinary methods — from AI analysis of drone imagery to ground-penetrating radar and LiDAR scans. While our focus has been on the historical implications, the technological means by which these sites were found illustrate archaeology’s evolving nature in the 21st century.

Finally, these cases underscore that historical understanding is provisional. Each discovery is a piece of a vast puzzle. The Magna Carta find teaches us to remain humble before archives; the Egyptian tombs remind us that well-known lands can still hide secrets; the South American sites show that entire chapters of human civilization may be awaiting discovery. As researchers continue to excavate, survey, and analyze, our view of history will only grow richer and more nuanced.

References

Harvard Law School’s ‘copy’ of Magna Carta revealed as original. Harvard Law School News. https://hls.harvard.edu/today/harvard-law-schools-copy-of-magna-carta-revealed-as-original/

“Harvard cut-price Magna Carta ‘copy’ now believed genuine.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm23zjknre7o

“Egyptian archaeologists discover three tombs in Luxor.” Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/egypt-luxor-necropolis-tombs-new-kingdom-8d9890225f73e8fa88bfa18ef0a2b62a

“Egypt discovers three New Kingdom tombs in Luxor’s Dra’ Abu El-Naga.” Daily News Egypt. https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2025/05/26/egypt-discovers-three-new-kingdom-tombs-in-luxors-dra-abu-el-naga/

“3 ancient Egyptian tombs dating to the New Kingdom discovered near Luxor.” Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/ancient-egyptians/3-ancient-egyptian-tombs-dating-to-the-new-kingdom-discovered-near-luxor

“Archaeologists use AI to discover 303 unknown geoglyphs near Nazca Lines.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/26/nazca-lines-peru-new-geoglyphs

“Major Discoveries at Chachapoya Site in Peru Announced.” Archaeology Magazine (Archaeological Institute of America). https://archaeology.org/news/2025/05/28/major-discoveries-announced-at-chachapoya-site-in-peru/

“Archaeologists Unearth 4,000-Year-Old Ceremonial Temple in Peru.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/archaeologists-unearth-4000-year-old-ceremonial-temple-in-peru-180984696/

“Huge ancient lost city found in the Amazon.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-67940671

“Lost cities of the Amazon: how science is revealing ancient garden towns hidden in the rainforest.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2025/feb/06/ancient-garden-cities-amazon-indigenous-technologies-archaeology-lost-civilisations-environment-terra-preta

“Researchers Have Found an Inca Tunnel Beneath the Peruvian City of Cusco.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/researchers-have-found-an-inca-tunnel-beneath-the-peruvian-city-of-cusco-180985872